Italiani nel Mondo

Nomi italiani e la perdita dell’Identità- Italian names and the loss of Identity

Nomi italiani e la perdita dell’Identità

Questo nuovo articolo è il frutto di un confronto tra Paolo Cinarelli il nostro editorialista da Buenos Aires, e me. Quando ho saputo di quel che stava per raccontare gli ho chiesto di scrivere un articolo e sono più che felice del risultato.

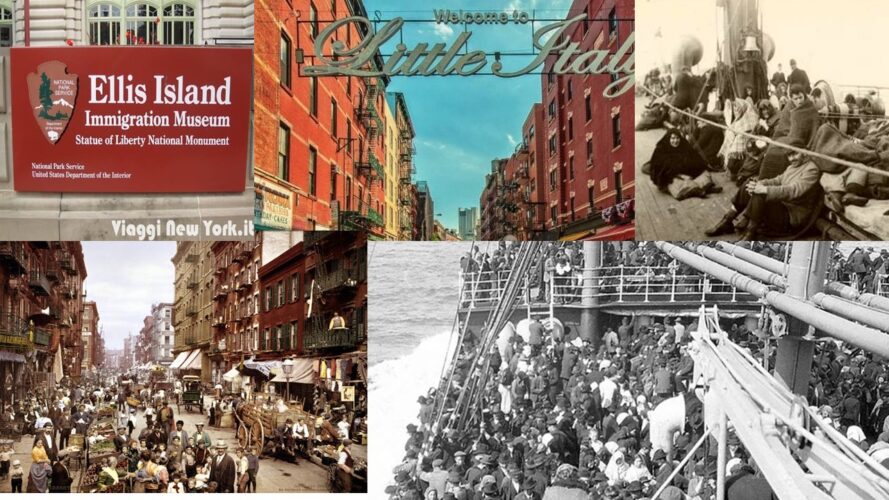

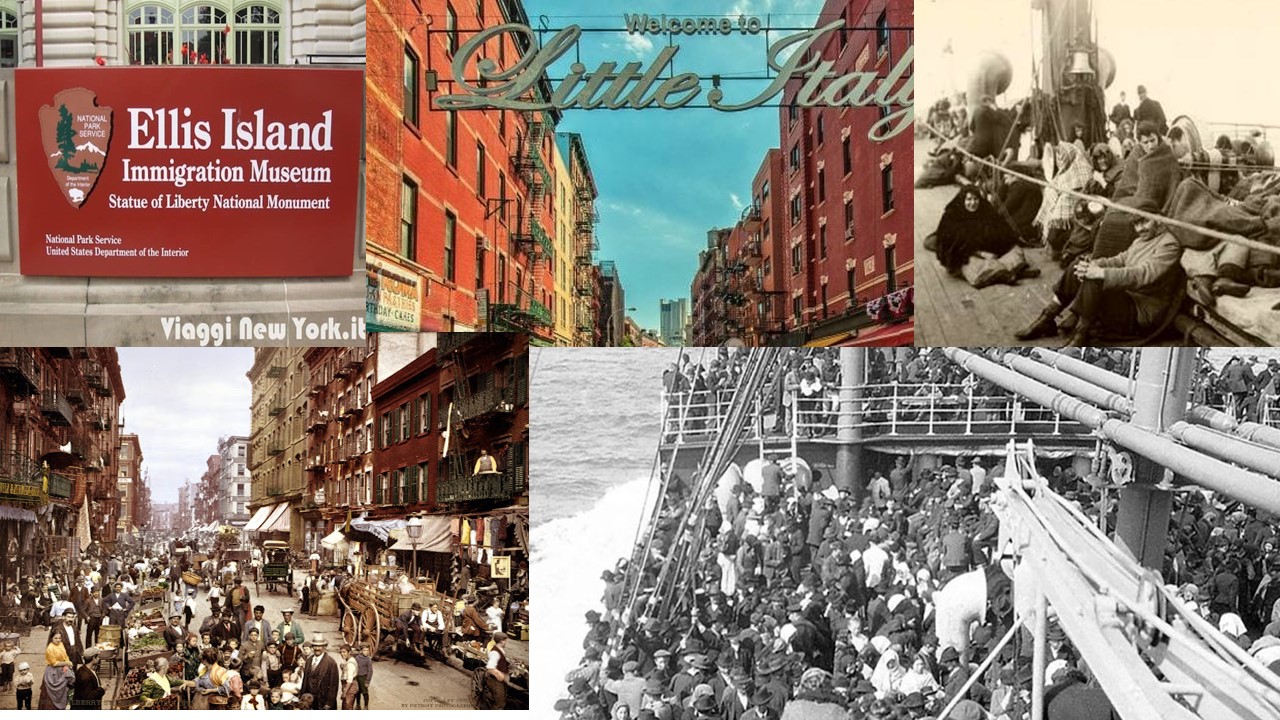

Senza rivelare l’accaduto posso dire che quel che succedeva in Argentina succedeva anche in altri paesi ed uno in particolare ha una delle comunità italiane più grandi nel mondo, il Brasile. Difatti, questo tema tocca un aspetto fondamentale dei figli/discendenti degli emigrati italiani, l’identità.

Il caso ha voluto che un paio di ore dopo l’arrivo di questo articolo un utente italo-americano ha fatto un commento su una pagina Facebook dedicata agli italiani in quel paese, che ha fornito un altro punto di vista su questa aspetto essenziale degli italiani all’estero.

L’utente ha spiegato un aspetto della vita di molte famiglie italo-americane che pochi conoscono, e che potrebbe essere una chiave per capire perché in molti modi le comunità italo-americane sono anomale paragonate a quelle in altri paesi, anglofone e non. Ed è così importante che il prossimo articolo tratterà il commento dell’utente americano ed altre considerazione delle anomalie americane.

Attenzione però, per evitare equivoci, quando parliamo di anomalie non intendiamo affatto un senso negativo, con un giudizio sull’accaduto, bensì intendiamo comportamenti diversi, nelle usanze, tradizioni e l’uso della lingua che potrebbero rivelare aspetti del loro passato che molti di noi oggigiorno non conoscono, e che potrebbero rivelare che la Storia delle comunità italo-americane, sia degli emigrati che dei loro figli/discendenti, non è mai stata quel che i luoghi comuni e gli stereotipi cercano di farci credere.

Infatti, questo articolo di Paolo sarà il primo di tre articoli che tratteranno aspetti dell’identità degli italiani all’estero, in modo particolare dei discendenti, spesso dimenticati, perché ci concentriamo così tanto su coloro che cercano la cittadinanza italiana che dimentichiamo che la maggior parte dei discendenti non hanno e non potranno avere diritto alla cittadinanza, e quindi anche il passaporto, ma non per questo motivo sentono meno il richiamo del paese di origine dei nonni e bisnonni, e ora cercano sempre di più di rintracciare le loro origini, comprese le prove del DNA che spesso danno risultati che confondono le idee invece di dare risposte definitive.

Allora chiediamo due favori ai nostri lettori mentre leggono questo articolo. Il primo è ovviamente di tenere ben in mente che i prossimi articoli forniranno altre considerazioni per sapere come agire nel futuro verso i nostri parenti ed amici all’estero. Il secondo favore è di ripetere il nostro invito ai lettori di inviarci le loro storie ed esperienze perché più sappiamo della realtà degli italiani all’estero più potremo fornire servizi ed informazioni che potranno far aumentare gli scambi tra le nostre comunità all’estero e l’Italia.

Inviate le vostre storie a: gianni.pezzano@thedailycases.com.

Nomi italiani, la perdita dell’Identità

Paolo Cinarelli

La pratica della rettifica del mio nome è durata tre anni e mezzo da quando l’impiegata addetta al rilascio dei documenti non ha più saputo come chiamarmi essendo nato Paolo, registrato alla frontiera come Paulo e infine iscritto all’anagrafe come Pablo. “Mi metta il nome che mi piace di più o anche tutti e tre”, le ho risposto senza dare troppa importanza ma non ha voluto sentire argomenti: andava fatta la rettifica. Era febbraio del 2008 e a luglio del 2011 ho finalmente avuto il documento con il mio vero nome, quello che porto dalla nascita. In quello stesso periodo l’Agenzia delle Entrate locale, l’Inps argentina e l’Aci mi avevano già iscritto come Pablo, ma restano dettagli minori.

In effetti, da Paolo a Pablo cambia solo una consonante, ma da Stefano e Esteban o da Calogero a Carlos le differenze sono notevoli e a volte ambigue. Il cambio del nominativo contrasta direttamente con la memoria storica costitutiva dell’identità di ogni persona. Molti hanno accettato l’imposizione del cambio o la traduzione come una nuova identità ma altri abbiamo fatto ricorso ai mezzi legali e/o istituzionali dando luogo alla giurisprudenza, che ha aperto la strada al riconoscimento del nome originale di ogni straniero.

Purtroppo fino a pochissimi anni fa in Argentina non erano permessi i nomi stranieri, la legge 18248 li bandiva e la modifica del 2012 è vigente dal 2015. Per una persona nata nel territorio e quindi cittadina dalla nascita è un argomento solo giustificabile dal punto di vista della dottrina che vuole una nazione in linea al concetto di Stato-nazionale, che non riconosce la coesistenza di diverse culture, in netto contrasto con l’origine migratoria della popolazione locale, non solo di provenienza oltreoceano ma anche dai paesi di confine e da regioni interne del paese. Nuovamente la giurisprudenza ha avuto un ruolo decisivo e il susseguirsi di sentenze favorevoli ai nomi non ispanici ha dato luogo a questa modifica del Codice Civile che ammette l’assegnazione di non oltre tre nomi, purché non siano offensivi e non si tratti di cognomi scambiati per nomi.

Spuntano a decine le storie di compaesani alle prese con i nomi dei loro figli, molti li hanno chiamati in modo neutro con nomi che rimangono uguali in entrambe le lingue. Questo è il motivo dei tanti Roberto, Mario, Enzo, Emilio, Antonio per i maschi e delle tante Maria, Claudia, Emilia e Daniela nelle prime generazioni di nati in Argentina. Spesso si vedono anche le traduzioni dei nomi più diffusi in Italia come Vicente per Vincenzo, Rafael per Raffaele o Ana per Anna. Alcuni nomi rimangono gli stessi ma cambiano secondo il genere e altri sono completamente diversi, per cui sarebbe sbagliato cercare una corrispondenza esatta tra le due lingue. Addirittura lo stesso nome può essere identificato a generi diversi secondo la lingua e spesso le persone preferiscono essere chiamate con nomi diversi secondo la lingua che parlano, è il tipo caso delle donne chiamate Andrea.

Una particolarità del tutto spagnola è la grande diffusione del doppio nome al punto che è molto raro trovare gente che ne porti solo uno. Ma la principale caratteristica è la grande diffusione di Maria come primo seguito da quello che passa ad essere quello distintivo, declassando il primo in un semplice arredo nominale: la quasi totalità delle donne dichiara di non riconoscersi con il solo nome Maria.

La novità è che da cinque anni è permesso dalla legge nominare i bambini Rocco, Vito, Matteo ma anche Chiara, Fiore e tra i tanti altri nomi. Adesso la scelta generazionale sembra orientarsi verso i nomi più corti, unici e semplici evitando nomi composti, lunghi e difficili da pronunciare. Questa tendenza viene confermata anche dalla scelta di altri nomi di tipo indigeno come Ailin, Nehuen, Nahuel, Lihuen.

Italian names and the loss of Identity

This new article is the result of a discussion between Paolo Cinarelli, our editorialist in Argentina, and me. When he told me the story he is about to tell I asked him to write an article about it and I am more than happy with the result.

Without giving away the details I can say that what happened in Argentina, a country with one of the world’s biggest Italian communities, also happened in other countries and in particular another country with one of the world’s biggest Italian communities, Brazil. In fact, this issue touches a fundamental aspect of the children/descendants of Italian migrants, identity.

As Fate would have it, two hours after the arrival of this article an Italo-American user made a comment on a Facebook page dedicated to the Italians in that country gave us another point of view on this issue that is fundamental for Italians overseas.

The user explained an aspect of the lives of many Italian American families that few know and that could be the key to understanding why in many ways that Italian American communities are anomalous compared to those in other countries, English language countries and not. And it is so important that the next article will deal with the comment of the user in America and other considerations on the American anomalies.

First however, in order to avoid misunderstandings we must point out that when we talk about anomalies we do not at all mean in a negative sense, or in judgment of what happened, but rather we mean different behaviours in regards to Italian customs, traditions and language that could reveal aspects of their past that many of us today do not know and that could also reveal that the history of the Italian American communities, both the migrants and their descendants, has never been what the clichés and the stereotypes try to make us understand.

In fact, this article by Paolo will be the first of three articles which will deal with the issue of the identity of Italians overseas, especially of the descendants who are often forgotten because we focus so much of those seeking Italian citizenship that we forget that the majority of the descendants do not have, and will never have, the right to Italian citizenship and therefore also the passport but this does not mean that they feel less the call of the country of their grandparents and great grandparents and now more and more of them are trying to look for for their roots, including DNA tests that often give results that confuse their ideas instead of giving definitive answers.

So, we ask two favours of our readers as they read this article. The first is obviously to bear in mind that the next two articles will provide other considerations to know how to act in the future towards our relatives and friends overseas. The second favour is to repeat our invitation to readers to send us their stories and experiences because the more we know about the realities of Italians overseas the more we will be able to provide services and information that will increase exchanges and between Italy and the Italian communities overseas.

Send your stories to: gianni.pezzano@thedailycases.com.

Italian names, the loss of Identity

by Paolo Cinarelli

The procedure to rectify my name lasted two and a half years from when the employee responsible for issuing documents no longer knew what to call me since as I born Paolo, registered at the border as Pablo and finally registered in the civil registry as Paulo. “Put the name you like the most or also all three” and I answered her without it giving too much importance but she did not want to hear any arguments, it had to be rectified. This was February 2008 and in July 2011 I finally had the document with my true name, the one that I have borne since birth. In the same period the local Tax Office, the Argentinean Social Security office and the ACI had already registered me as Pablo but these are trivial details.

Effectively only one consonant changes from Paolo to Pablo but from Stefano in Italian to Esteban in Spanish or from Calogero in Italian to Carlos the differences in consonants are notable and at time ambiguous. The change of names contrasts directly with the integral memory that makes up the identity of each person. Many accepted the imposition and the change or the translation as a new identity but others of us appealed by legal and/or institutional means that gave rise to the jurisprudence which paved the way for the recognition of the original name of every foreigner.

Unfortunately, until a very few short years ago foreign names were not allowed in Argentina, law number 18248 banned them and the 2012 amendment has been in force since 2015. For a person born in the country and therefore a citizen by birth this argument can only be justified by the doctrine of a nation in line with the concept of State-nation that does not recognize the coexistence of different cultures which is in stark contrast with the migrant origin of the local population that came not only from other continents but also from neighbouring countries and between regions within the country. Once again jurisprudence played a decisive role and the succession of sentences that favoured the non-Hispanic names led to this amendment of the Civil Code that allowed the attribution of no more than three names, as long as they were not offensive and that surnames were not mistaken for names.

There are dozens of stories of our countrymen who struggled with the names of their children, many of them naming them in a neutral way with names that are the same in both languages. This is the reason for the many children named Roberto, Mario, Enzo, and Antonio for the males and the many girls called Maria, Claudia, Emilia and Daniela in the first generations born in Argentina. Often we also saw the translation of the more popular names in Italy such as Vicente for Vincenzo in Italian, Rafael for Raffaele in Italian or Ana for Anna. Some names stayed the same but changed according to gender and others were completely different for which it would be wrong to try to look for an exact match between the two languages. Indeed, the same name can be called in different ways according to the language spoken and often people prefer being called with the different names according to the languages they speak, this is the case of women named Andrea, which in Italian is a purely male name.

One particularity that is all Spanish is the great distribution of the double name to the point that it is very rare to find people who have only one. But the main characteristic is the great distribution of Maria as the first name followed by the one that would pass as the distinctive name which declassifies the first into a simple nominal element, almost all the women state that they do not recognize themselves with only the name Maria.

The new development is that over the last five years the law has allowed children to be named Rocco, Vito, Matteo and also Chiara, Fiore or one of many other names. Now the choice of the current generation is aimed on shorter, unique and simpler names that avoid composite, long or difficult to pronounce names. This trend has also been confirmed by the choice of other indigenous type names such as Ailin, Nehuen, Nahuel and Lihuen.