Diritti umani

Intervista a Federico Storani su Raúl Alfonsín, Néstor Kirchner e i Diritti Umani- An interview with Federico Storani about Raúl Alfonsín, Néstor Kirchner and Human Rights

Intervista a Federico Storani su Raúl Alfonsín, Néstor Kirchner e i Diritti Umani

di Edda Cinarelli

In un momento in cui in Argentina abbiamo una democrazia di scarsa intensità con un Presidente, Javier Milei, autoritario, violento, maltrattatore, classista che ricorre al veto per fermare le leggi approvate dal “Congreso” e ha anche nominato ministro dell’Interno Lisandro Catalán, figlio di un funzionario della passata dittatura, è consigliabile per proteggere la propria salute mentale ricordare periodi in cui accadevano processi inversi, come quelli diretti da Raúl Alfonsín, primo presidente (1983 – 1989) eletto dopo la dittatura e Néstor Kirchner (2003 – 2007) che ha riaperto i processi ai colpevoli di crimini di lesa umanità.

Ne parliamo con Federico Storani, professore, titolare per concorso di Diritto nell’Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Politico molto conosciuto e quasi familiare soprattutto perché faceva parte del governo di Raùl Alfonsín. Deputato nazionale dal 1983 al 1991, presidente della Comisión de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto dal 1983 al 1989. Ha svolto un ruolo importante nel Tratado Limite (Trattato dei confini) con il Cile.

Federico Storani

Raúl Alfonsín (1927-2009) è stato il primo Presidente eletto democraticamente dopo la Dittatura. Avvocato con la passione per la politica ed una forte vocazione di servizio è passato alla storia come il Presidente che ha pilotato l’Argentina dalla dittatura alla democrazia e probabilmente l’ultimo di quelli che non si sono arricchiti durante la loro gestione. Il 18 dicembre 1975, tre mesi prima del Golpe, è stato co-fondatore della Asamblea Permanente por los Derechos Humanos (Assemblea Permanente dei Diritti Umani) che da allora ha sempre difeso.

Nel 1983, quando si è saputo che aveva vinto le elezioni, la popolazione è esplosa in preda ad una esaltazione contagiosa, era come se una brezza di felicità soffiasse per tutto il Paese. La gente si è riversata in Piazza della Repubblica per cantare, ballare, esprimere gioia e c’è stato anche chi per l’ebbrezza si è arrampicato sull’Obelisco, ubicato nel mezzo della piazza, per osservare la folla esultante. Alfonsin è passato alla storia per il suo coraggio, la sua determinazione ma anche la sua predisposizione al dialogo.

Assemblea Permanente dei Diritti Umani

Dirigente della Unión Cívica Radical (UCR), si è imposto su Italo Luder, candidato del Partito Peronista, grazie ad un messaggio di tolleranza e di speranza, che era piaciuto alla popolazione stanca di sette anni di dittatura, di feroce repressione e molti Desaparecidos.

Dulcis in fundo, la guerra delle Malvinas/ Falklands (2 aprile 1982 – 14 giugno 1982) è stata la goccia che ha fatto traboccare il vaso, un tentativo dei militari per generare consenso e restare al potere, finito in una sconfitta argentina e in una cocente delusione e in un’altra mortificazione per gli argentini.

Alfonsin è stato l’unico politico importante a non sommarsi al coro nazional-militarista durante la Guerra di Malvinas, divenuto Presidente ha avuto il coraggio di affrontare i militari, piegati dalla sconfitta in guerra ma ancora forti, orgogliosi e riottosi a lasciare il potere e ad accettare la supremazia di un Presidente, eletto democraticamente. Lui li ha fatti giudicare e loro insofferenti gli hanno risposto con varie insubordinazioni, passate alla storia come Carapintada, quasi a volergli mostrare i denti e dirgli: Ti facciamo vedere chi comanda.

Come se fosse poco se l’è dovuta vedere con una serie di scioperi indetti da Saúl Ubaldini, segretario generale della Confederacion General del Trabajo (CGT 1986 – 1990) e con i grandi imprenditori che gli hanno reso difficile la gestione. La società nel suo insieme si è stancata della iperinflazione ed il settore di centro sinistra si è sentito deluso dall’atteggiamento dialoghista, erroneamente interpretato per debolezza, di Alfonsín, mentre quello di destra appoggiava i militari.

Durante la sua presidenza ha realizzato il processo a las Juntas Militares, che si erano succedute al potere dal 1976 al 1983. Ha presentato i disegni di legge per trasformare l’Argentina da una Repubblica Presidenziale ad una Repubblica democratica e per trasferire la capitale della Repubblica da Buenos Aires a Viedma, una città del Rio Negro.

I militari con le loro ribellioni e minacce sono riusciti a fargli emanare le leggi di Punto Final e di Obediencia Debida che hanno messo a rischio la giovane democrazia. In quanto alle Relazioni con l’estero ha avviato l’asse di integrazione Argentina-Brasil-Uruguay, inizio del MERCOSUR, consolidato con la firma del Trattato di Asuncion 26 marzo 1991.

–Tra la popolazione è diffusa la convinzione che sia stato Néstor Kirchner, il Presidente che ha lottato di più per fare giustizia nel campo dei Diritti Umani mentre mi ricordo del Nunca Mas, con il prologo di Ernesto Sabato, e del Processo a Las Juntas del 1985, epoca di Alfonsin. Cos’è successo?

Bisogna contestualizzare l’accaduto storicamente. Se nel 1983 avesse vinto il Peronismo e Luder fosse stato eletto Presidente non ci sarebbe stato né il Nunca Mas né il Processo a las Juntas Militares ed è doveroso ricordare che Kirchner sosteneva la posizione di Luder.

In questo tema Alfonsin e Luder avevano due proposte contrastanti. Alfonsin proponeva l’annullamento de la Ley de Pacificacion Nacional (Legge Nazionale di Pacificazione, il 22 settembre 1983) che era praticamente un’auto amnistia. Luder sosteneva che non si poteva annullare perché era passata in giudicato quindi se avesse vinto Luder non ci sarebbe stato il Nunca Màs e non ci sarebbe stato il processo ai militari. Kirchner condivideva l’opinione di Luder. Di tutto questo ci sono i documenti, le prove.

–Quindi Alfonsín ha avuto un coraggio enorme?

Certamente un coraggio senza paragoni e grazie a questo coraggio ha potuto pilotare una transizione di rottura dall’autoritarismo alla democrazia. Di rottura vuol dire non negoziata. Non è stato come in Cile dove Pinochet ha perso un plebiscito ed ha dovuto andarsene. Qui la dittatura è caduta per la sconfitta militare nelle Malvinas, i militari sono stati sconfitti ma erano ancora forti ed organizzati e Raúl Alfonsín li ha affrontati.

–Come ha fatto? Che passi ha seguito

È riuscito a processare las Juntas Militares attraverso dei decreti e delle azioni, che gli hanno permesso di portare a capo un processo giuridico senza precedenti nel mondo e a mantenere così la promessa fatta in campagna di restaurare lo Stato di Diritto e la Giustizia interrotti dal Golpe del 1976.

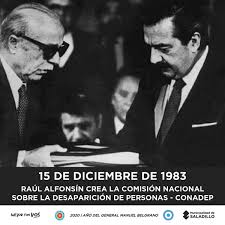

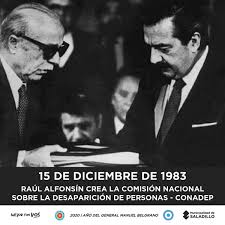

Primo: cinque giorni dopo aver assunto la presidenza, in qualità di Comandante in capo delle Forze Armate e Presidente costituzionale ha accusato las Juntas Militares per violazione dei Diritti Umani, cioè ha aperto il processo.

Secondo: ha mandato il disegno di legge per abrogare l’auto amnistia e ha creato l’istanza che consentiva alle Forze Armate di giudicarsi da sole, siccome si sono rifiutate di farlo ha fatto giudicare i militari da tribunali civili.

Terzo: ha creato simultaneamente la Comision Nacional sobre la desaparición de personas (CONADEP) formata da persone di spicco di diversi ambiti della società argentina e da tre deputati radicali. In quel momento ero deputato ed Alfonsin mi ha affidato il compito di invitare gli altri blocchi, compreso quello peronista ad entrare nel gruppo, ma i peronisti non hanno voluto farne parte.

–Quindi la Storia è questa?

La posso raccontare come testimone. I peronisti non hanno voluto farne parte e ci hanno lasciati soli. Il rapporto della CONADEP è stato la base dell’accusa del procuratore Julio Cèsar Strassera per portare avanti il processo e arrivare alla condanna dei responsabili dei crimini in poco tempo. Il processo è iniziato il 22 aprile 1985 ed è finito il 9 dicembre 1985 con una sentenza di condanna. Hanno testimoniato 839 persone. E’stata l’unica volta in America Latina in cui un governo democratico ha giudicato i membri del governo dittatoriale che l’ha preceduto.

–Paragone tra Alfonsín e Kirchner?

Non è possibile fare un paragone perché Kirchner ha cacciato le lepri in uno zoo e noi cacciavamo i leoni sciolti. Naturalmente apprezzo l’azione meritoria di Kirchner però bisogna contestualizzarla. Se avesse vinto Luder i responsabili dei crimini di Lesa Umanità non sarebbero stati giudicati e condannati.

–Credo che per capire quello che è successo bisogna fare un accenno a Menem, Presidente dal 1989 al 1999, che ha dato l’indulto ai militari ed ai guerriglieri ma togliendo il servizio militare obbligatorio (1994) ha indebolito i miliari. Pensa che Menem sia stato un opportunista?

Era un opportunista politico. Nel 2004 ha realizzato davanti alla porta de la Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA, Scuola di Meccanica della Marina Militare, luogo di molti dei crimini contro l’Umanità ), una cerimonia in cui ha chiesto perdono perché durante venti anni non si era fatto niente in questo campo. Poi ha telefonato ad Alfonsín per chiedergli scusa, al che Alfonsín ha risposto che le offese pubbliche si rispondono pubblicamente e non in privato. È evidente che non ci sarebbe stato nessun processo senza la esistenza di Raúl Alfonsín.

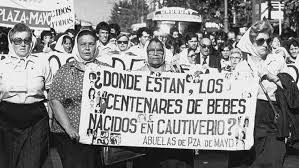

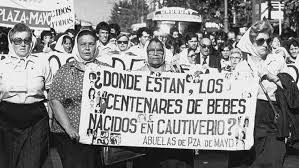

–Crede che le Associazioni Madres y Abuelas siano state opportuniste?

No, e meno che meno lo penso per Asociación Abuelas. Nel caso di Estela Carlotto, che conosco bene perché è di La Plata come me, sono sicuro che non è stata opportunista.

Penso che in qualche momento questi gruppi siano caduti nel settarismo e che se i Diritti Umani, che sono universali, diventano esclusivi di alcune associazioni perdono importanza.

–Alcune persone dicono che Alfonsin non avrebbe dovuto fare il Pacto di Olivos.

Personalmente credo che il Pacto di Olivos sia stato un errore. Alfonsín ha scritto un libro per spiegare le ragioni che l’hanno mosso a stringere questo patto. Ha scritto che Menem avrebbe realizzato a tutti i costi la riforma costituzione perché cercava la rielezione; quindi, ha pensato che fosse meglio dialogare con lui per ottenere un risultato il più positivo possibile.

Menem voleva la rielezione, infatti è stato eletto due volte e ci ha provato per la terza e così come avrebbe violato l’anteriore Costituzione ha violato quella nuova. Menem era un invertebrato morale non gli importava niente.

An interview with Federico Storani about Raúl Alfonsín, Néstor Kirchner and Human Rights

by Edda Cinarelli

At a time when we in Argentina have a weak democracy with an authoritarian, violent, abusive and classist president, Javier Milei, who uses his vetoes to block laws approved by the “Congreso” and has even appointed as Interior Minister Lisandro Catalán, son of a functionary of the past dictatorship, it is advisable for the sake of protecting our mental health to remember periods in which the opposite was true, such as those led by Raúl Alfonsín, the first President (1983 – 1989) elected after the dictatorship, and Néstor Kirchner (2003 – 2007) who reopened the trials of those guilty of crimes against Humanity.

We discussed this with Professor Federico Storani, Head of the Faculty of Law at the University of La Plata. He is a well-known and an almost household name mainly because he was part of Raùl Alfonsín’s Government. He was a Deputy of the National Parliament from 1983 to 1991, Chairman of the Comisión de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto (Foreign Affairs and Worship Commission) from 1983 to 1989. He also played an important role in the Border Treaty with Chile.

Raúl Alfonsín (1927-2009) was the first President elected democratically after the Dictatorship. A lawyer with a passion for politics and a strong vocation for public service, he went down in history as the President who led Argentina from dictatorship to democracy and was probably the last of those who did not enrich themselves during their term of office. On September 18, 1975, three months before the Coup, he was the co-founder of the Asamblea Permanente por los Derechos Humanos (Permanent Assembly for Human Rights) which he has always defended ever since.

In 1983, when it was announced that he had won the election, the population exploded with contagious excitement, it was like a breeze of happiness blowing across the whole country. The people went to Plaza de la Republica to sing, dance and show their joy, and there were even those who climbed onto the Obelisk in the middle of the square to watch the jubilant crowd. Alfonsín went down in history for his courage, his determination and for his willingness to engage in dialogue.

A leader of the Unión Cívica Radical (UCR, Radical Civic Union), he prevailed over Italo Luder, the Peronist party candidate, thanks to a message of tolerance and hope that appealed to the population weary of seven years of dictatorship, ferocious repression and many Desaparecidos (missing persons).

Last but not least, the War of the Malvinas/Falklands (April 2, 1982 – June 14, 1982) was the straw that broke the camel’s back, an attempt by the military to generate popular consensus and to remain in power that ended with an Argentine defeat, burning disappointment and further mortification for Argentineans.

Alfonsín was the only important politician who did not join the nationalist-militarist choir during the War for the Malvinas. Once he became President, he had the courage to confront the military who were weakened by the defeat in the war but still strong, proud and unwilling to relinquish power and accept the supremacy of a democratically elected President. He brought them to trial and the hostile ones responded with various acts of insubordination, which went down in history as the Carapintada, almost as if they wanted to bare their teeth at him and say, “We will show you who is in charge”.

As if that were not enough, he had to deal with a series of strikes called by Saúl Ubaldini, Secretary General of the Confederacion General del Trabajo (CGT, General Federation of Work 1986 – 1990) and with big business leaders who made it hard for him to govern.

Society as a whole grew tired of hyperinflation, and the centre-left was disappointed in Alfonsín’s conciliatory attitude which was wrongly interpreted as weakness on the part of Alfonsín, while the right wing supported the military.

During his presidency he brought to trial las Juntas Militares (the Military Juntas) that had ruled the country from 1976 to 1983. He introduced Bills to transform Argentina from a Presidential Republic to a democratic Republic and to move the Capital of the Republic from Buenos Aires to Viedma, a city in Rio Negro.

With their rebellions and their threats, the military managed to make him enact the Punto Final and Obediencia Debida Laws that jeopardized the young democracy. As for Foreign Relations, he launched the Argentina-Brazil-Uruguay axis of integration, started the MERCOSUR, which was consolidated by the signing of the Treaty of Asuncion on March 26, 1991.

– There is a widespread belief that it was Néstor Kirchner, the President who fought the hardest for justice in the field of Human Rights, while I remember Nunca Mas, with Ernesto Sabato’s prologue, and the trial of Las Juntas in 1985, during Alfonsín’s era. What happened?

We need to put what happened into historical context. If Peronism had won in 1983 and Luder had been elected President, there would not have been neither Nunca Mas, nor the Trial of Las Juntas and it is important to remember that Kirchner supported Luder’s position

On this issue Alfonsín and Luder had two conflicting proposals. Alfonsín proposed repealing the Ley de Pacificacion Nacional (National Reconciliation Law, 22 September 1983), which was essentially a self-amnesty. Luder maintained that it could not be repealed because it had already become final. So, if Luder had won there would have been no Nunca Mas and no trial of the military. Kirchner shared Luder’s opinion. There are documents and evidence of all this.

– So Alfonsín showed enormous courage?

Certainly, he had unparalleled courage and thanks to this courage he was able to lead a radical transition from authoritarianism to democracy. Radical means unnegotiated. It was not like Chile, where Pinochet lost a plebiscite and had to leave. Here the dictatorship fell due to the military defeat in the Malvinas; the military were defeated, but they were still strong and organized, and Raúl Alfonsín confronted them.

– How did he do it? What steps did he take?

He succeeded by prosecuting the Juntas Militares through decrees and actions, which enabled him to carry out a legal process without precedent in the world, and thus he kept the promise he made during the electoral campaign to restore the Rule of Law and Justice which had been interrupted by the 1976 Coup d’état.

First: five days after assuming the presidency as the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces and Constitutional president, he accused the Juntas Militares of violating Human Rights, in other words, he opened the trial.

Second: he sent the Bill to repeal the self-amnesty and created the act that allowed the Armed Forces to judge themselves. Since they refused to do this, he had the military judged by civil courts.

Third: at the same time, he created the Comision Nacional sobre la desaparición de personas (CONADEP, National Commission on the disappearance of Persons) made up of prominent figures from various sectors of Argentine society and three Radical Party Members of Parliament. At that time, I was a Member of Parliament and Alfonsín entrusted me with the task of inviting other blocs, including the Peronists, to join the group. But the Peronists did not want to be part of it.

– So, this is history?

I can tell this as a witness. The Peronists did not want to be involved, and they left us alone. The CONADEP Report formed the basis for the indictment by Prosecutor Julio Cèsar Strassera to start the trial and secure the conviction of those responsible for the crimes in a short time. The trial started on April 22, 1985, and ended on December 9, 1985, with a conviction. A total of 839 people testified. It was the only time in South America that a democratic government tried members of the dictatorial government that proceeded it.

– The comparison between Alfonsín and Kirchner?

It is impossible to make a comparison because Kirshner hunted hares in a zoo, and we hunted lions in the wild. Of course, I appreciate Kirchner’s commendable action, but it must be put into context. If Luder had won, those responsible for crimes against Humanity would never have been tried and condemned.

– I believe that to understand what happened a mention must be made of Menem, President from 1989 to 1999, he granted amnesty to the military and guerilla fighters but, by abolishing compulsory military service (1994), he weakened the military. Do you think that Menem was an opportunist?

He was a political opportunist. In 2002 he created in front of the door of the Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (ESMA, Navy School of Mechanics, where many of the crimes against Humanity occurred ) and he asked for forgiveness because he did nothing in this area for twenty years. He then telephoned Alfonsín to apologize to which Alfonsín replied that public offences should be answered in public and not privately. It is clear that that there would have been no trial without Raúl Alfonsín.

–Do you believe that the Madres y Abuelas Associations were opportunistic?

No, I certainly do not believe that about the Abuelas Associations. In the case of Estella Carlotto, who I know because she was from La Plata like me, I am sure she was not being opportunistic.

I think that at some point these groups fell into sectarianism and that if is Human Rights, which are universal, become the exclusive domain of certain associations, they lose their importance.

–Some people say that Alfonsín should not have made the Olivos Pact

Personally, I believe that the Pacto de Olivos (Olivos Pact of 1993) was a mistake, Alfonsín wrote a book to explain the reasons that led him to sign this pact. He wrote that Menem would have carried out constitutional reform at all costs because was seeking re-election; so, he thought that it would be better to engage in dialogue with him to achieve the most positive outcome possible.

Menem wanted to be re-elected. In fact, he was elected twice, and he tried for a third time violating the new Constitution, just as he violated the previous one. Menem was morally spineless; he did not care about anything.